The Devils Review

One thing I truly love about cinema is the way in which films can make an audience think, to ignite a spark in their minds, provoking thoughts that never would have occurred otherwise and send them off in new directions, contemplating new ideas and viewpoints. One of the most exciting ways that cinema often achieves this is through confrontation, dangerous and exciting cinema that pulls no punches and feels dangerous.

One thing I truly love about cinema is the way in which films can make an audience think, to ignite a spark in their minds, provoking thoughts that never would have occurred otherwise and send them off in new directions, contemplating new ideas and viewpoints. One of the most exciting ways that cinema often achieves this is through confrontation, dangerous and exciting cinema that pulls no punches and feels dangerous.

One such dangerous film is Ken Russell’s 1971 The Devils, screened last week as part of Montreal’s Fantasia Film Festival with Ken Russell himself in attendance. The film takes place in 17th century France and focuses on Father Grandier, played by Oliver Reed giving probably the best performance of his career. Grandier is a sexually adventurous priest who, despite what appears to be genuine faith and devotion to god, pushes the boundaries of what is morally acceptable at the time, in the process becoming a scapegoat, caught in a political game which can only end with his destruction. Oliver Reed is joined by a fantastic supporting cast which includes Vanessa Redgrave, Dudley Sutton, Gemma Jones, Michael Gothard and a wonderful performance by Murray Melvin as Mignon.

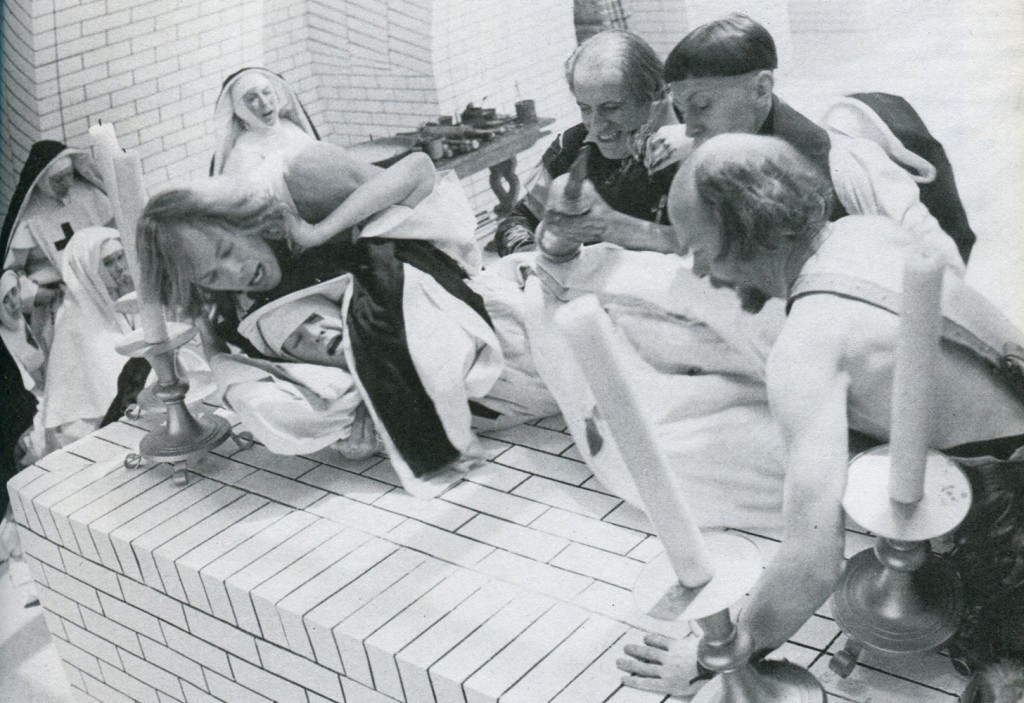

As Grandier’s home, the city of Loudon, descends into anarchy, superstition and insanity, the film becomes more and more intense but never lapsing into too much of the visual extravagance that characterized Russell’s other films such as Lisztomania or Tommy. This is important here as it helps ground the film and never lets the audience treat it as fantasy or mere exploitative provocation.

Banned or cut across the world on its original release The Devils is still incredibly hard to find and even at a festival where the notorious A Serbian Film is playing, The Devils presented the organisers with serious problems in obtaining a print to show. Warner Brothers currently hold the rights to the film which is completely unavailable anywhere in the cut that Russell intended. The version I saw at Fantasia was unfortunately a shorter theatrical cut but even in its censored form the film still had power and presence. Before the film began Russell asked the audience who had never seen The Devils before and almost half the audience raised their hands. With three standing ovations (although one was before the film) I think it is safe to say that the audience were enraptured by the film and despite the fact that I’d seen the film a number of times before it was a welcome reminder of how powerful the film actually is and in places how entertaining.

Visually striking set designs from Derek Jarman, a hallucinatory score by Peter Maxwell Davies and Russell’s off kilter direction make this a cinematic experience that is unforgettable but it is in the script that a lot of the power and brilliance of the film lies. Take a look at the following line uttered by Father Grandier and you can see that the controversy surrounding The Devils is not just due to the nuns on a psycho-sexual rampage but it is in the provocative critical approach the film takes to religion;

Most religions believe that by crying, “Lord, Lord!” often enough, they can contrive to enter the kingdom of heaven. A flock of trained parrots could just as readily cry the same thing with just as little chance of success.

With the far right extremist religious fringes becoming more and more mainstream, especially in American politics, the film is as relevant, provocative and powerful today as it was in 1971.